Age of Empire

A time of empire, colonialism, and slavery

The Age of Empire was a time of great change and progress, but this progress came at the cost of great injustice and suffering.

Everything was interconnected. Alongside the slave trade and expansion of the British Empire there were advancements in machinery and steam power. These enabled the processing of raw materials such as cotton, and created a new working class, who often worked in terrible conditions.

In this age of progress, borne on the backs of the enslaved and the working poor, Scotland played its part.

Glenfinnan Viaduct / Drochaid-rèile Gleann Fhionnainn

Glenfinnan Viaduct / Drochaid-rèile Gleann Fhionnainn by Rudi from Bun-Sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar.

Asia

In 1600 the Honourable East India Company was formed by Royal Assent (permission given by Queen Elizabeth the 1st of England).

The East India Company was supposed to be a trading corporation, but it grew into something much more powerful. It had its own armies, and, together with unfair and forceful trading practices, swept away rulers that stood in its path. It became tremendously powerful and took over most of India, causing a lot of suffering and impoverishment. For example, they forced the skilled cotton muslin weavers of India to trade only with them, and imposed high taxes, until they had destroyed this three-thousand-year-old craft.

The East India Company also used force to colonise other parts of Asia, such as Hong Kong, Singapore, Burma and parts of Malaysia. The Chinese were forced to trade in opium, a strong drug, against their will, which resulted in a short war. The British Navy bombarded the Chinese ports until they had to accept defeat.

The British government took much more interest in India after losing its colonies in America.

In India, there was a rebellion against the British in 1857, called a ‘mutiny’, which was very violent. This led to the East India Company being taken over by the Crown, and from then on, colonies were directly ruled by Queen Victoria.

Queen Victoria was declared Empress of India in 1874. The Indian people were told that they would have an equal say in running their country, but this did not happen. What do you think of this picture? Does this look like two equal partners?

India eventually regained its independence in 1947, following the campaign of peaceful resistance led by Mahatma Ghandi.

America

The first British colony in America was established at Jamestown in Virginia in 1607. It was named after Scottish King James the 6th and 1st, son of Mary Queen of Scots.

The new settlers learned about tobacco smoking from the Native American people, and soon took to smoking pipes. Tobacco began to be sent back to Britain, where the craze caught on. As the settlers found out they could make lots of money from growing and selling tobacco, the population surged.

Many thousands of convicts, including prisoners of war, were shipped out to the colonies to provide cheap labour. Soon people were flooding into

America from Britain and the rest of Europe. Most were poor, ordinary people including many Scots, and Highlanders from Lochaber.

It was a different story for the rich. Wealthy people bought land for tobacco and cotton plantations, and slaves were used as the main workforce.

America won its independence from Britain in 1776.

Slavery continued in the American South until the Civil War in the 1860’s. It was finally banned in 1863.

Britain had officially banned slavery in 1833, but was still buying most of their tobacco and cotton grown with slave labour from America. So, Britain was still profiting from slavery until the 1860’s.

The Caribbean & rest of world

Britain also established colonies throughout the Caribbean islands, which became very profitable as a place for growing and refining sugar.

What do you think of when you hear ‘history of the Caribbean’? Maybe beaches, palm trees..and pirates! But the reality was a horrific one. Many thousands of enslaved Africans were captured and brought here to work in unimaginably horrible conditions. Those who survived the terrible sea voyage often died within three years.

Many territories in Africa also came under British rule.

Colonies were also founded in Canada, Australia and New Zealand – that is why these are English-speaking countries.

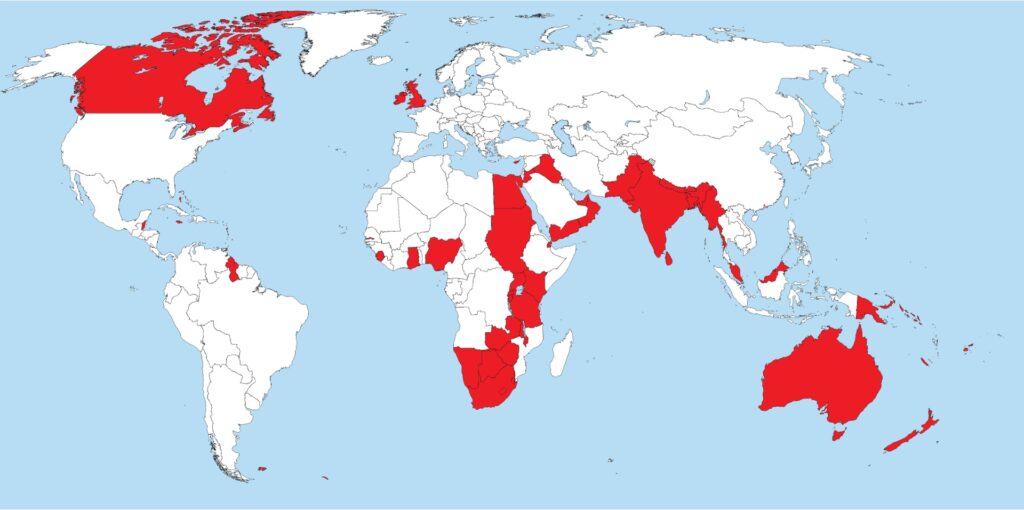

You might have heard of the ‘Commonwealth’, perhaps the Commonwealth Games. This is a group of 56 countries who were formerly part of the British Empire, and who still have the King or Queen as their official Head of State.

At the height of its power, the British Empire ruled a quarter of the world. You can see that these two maps are almost the same.

Britain had a mighty navy which allowed it to become a superpower.

This mighty trading Empire was driven by colonialism and financed by the labour of enslaved people.

What does ‘enslaved’ mean?

‘Chattel slavery’ means people who were legally defined as the personal property of their owner. They could be bought, sold, and split up from their families. They were forced to work hard and often treated very badly.

The transatlantic slave trade is a terrible stain on the history of humanity. Around 12 million human beings were captured and sold, in horrible conditions.

How on earth was this terrible trade in human lives possible? Slavery has always existed, in almost every society, since ancient times. But it had never been seen on this industrial scale in the history of humanity, until the 18th and 19th centuries.

The slave trade began with Portuguese and Spanish traders capturing African people, and transporting them to their South American colonies.

In the 16th century, English pirates started selling enslaved people to the Spanish colonies.

Britain soon became the main slave trading nation. The trade reached its height in the 1790’s. The money pouring in allowed some people to get very rich, and working with goods like cotton and tobacco gave employment to many thousands of working class people.

A Scottish slave trading captain actually named his ship after his daughter – this shows he thought it was fine to be a slave trader, and nothing to be ashamed of.

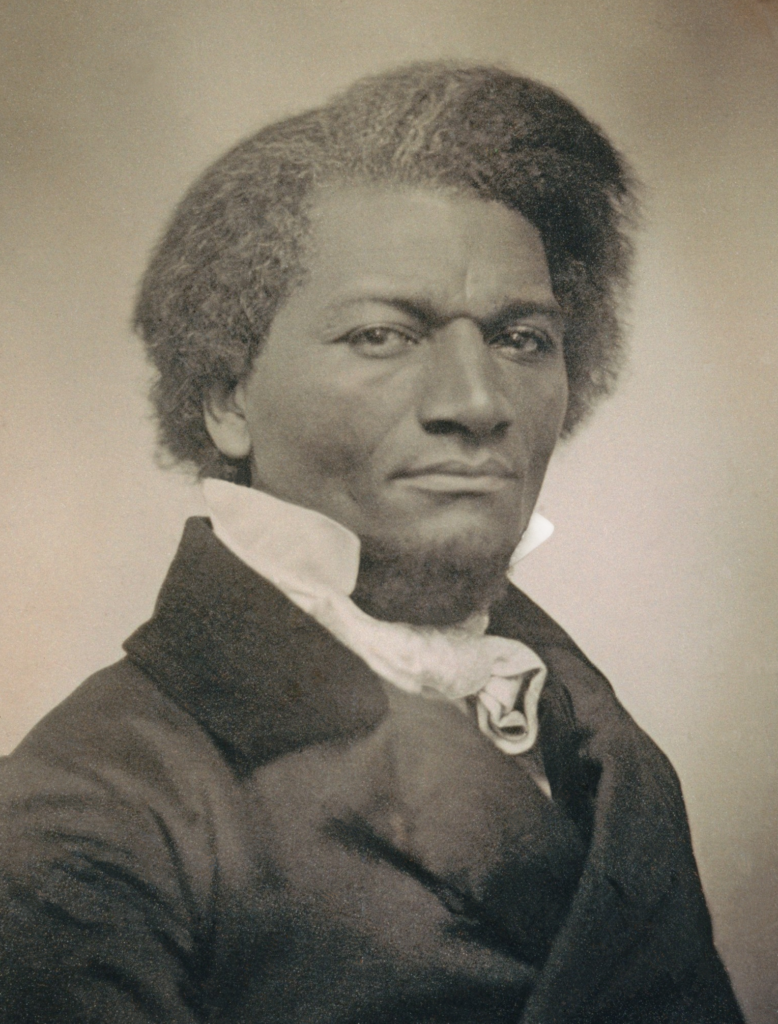

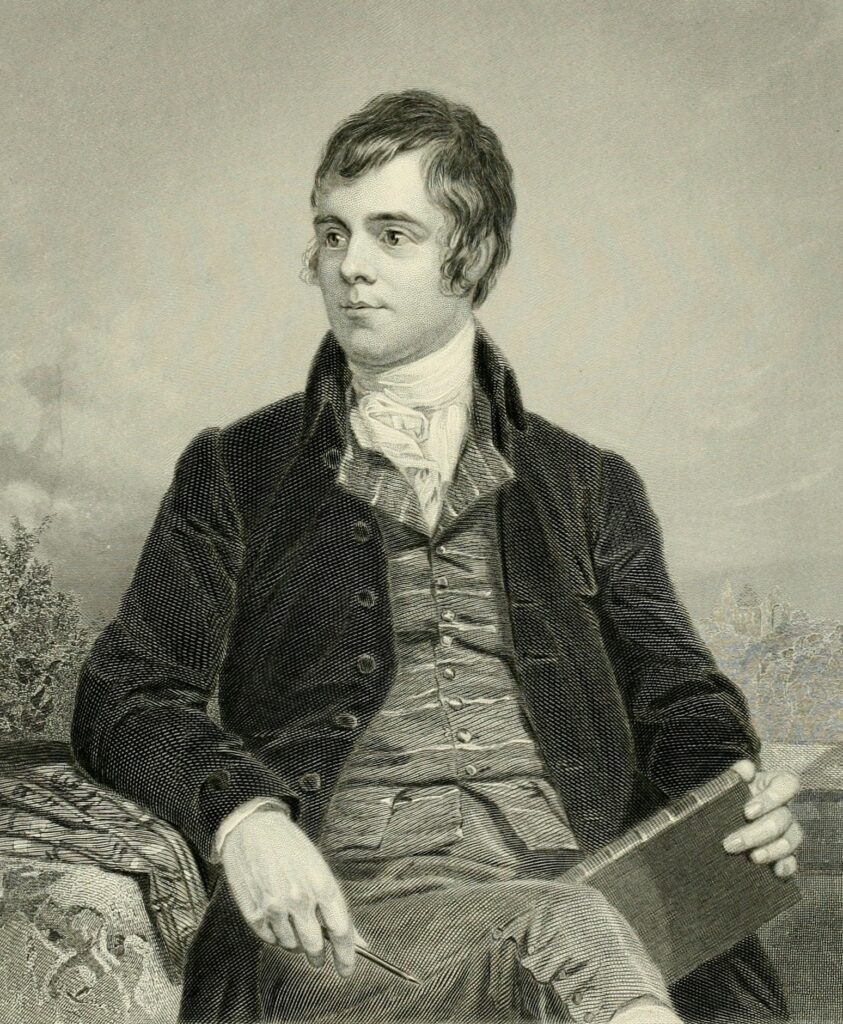

However, many decent people were horrified at what was going on, and became abolitionists. Frederick Douglas from Maryland in America, was a former slave who became an abolitionist leader. He was inspired by the words of Robert Burns, Scotland’s national poet; ‘A man’s a man for a’ that’. In the 1840’s, Douglas toured all over Scotland giving speeches. Burns had published an anti-slavery poem, The Slave’s Lament, in 1792, the first verse of which read: ‘It was in sweet Senegal that my foes did me enthral,/For the lands of Virginia, /O Torn from that lovely shore, and must never see it more’.

Scotland

How did Scotland play its part specifically? What about ordinary, poor working class people – surely it was nothing to do with them?

It’s true that such people also suffered during this period, often due to exploitative working conditions, down mines or in industrial mills.

Poverty, hunger, disease and insanitary housing were commonplace. Highlanders who’d been cleared from their lands found themselves living in the slums of Glasgow, their children hungry and in rags. Children were coming to school barefoot even in the 1930’s. New diseases of urban squalor such as tuberculosis, typhoid and cholera were killers.

Yet even poor people could be caught up in the slave economy, becoming both victims and perpetrators in the Age of Empire.

Working with slave-grown goods like cotton and tobacco gave employment to many thousands of working class people.

Scotland’s working class could be employed in manufacturing things specifically for slaves.

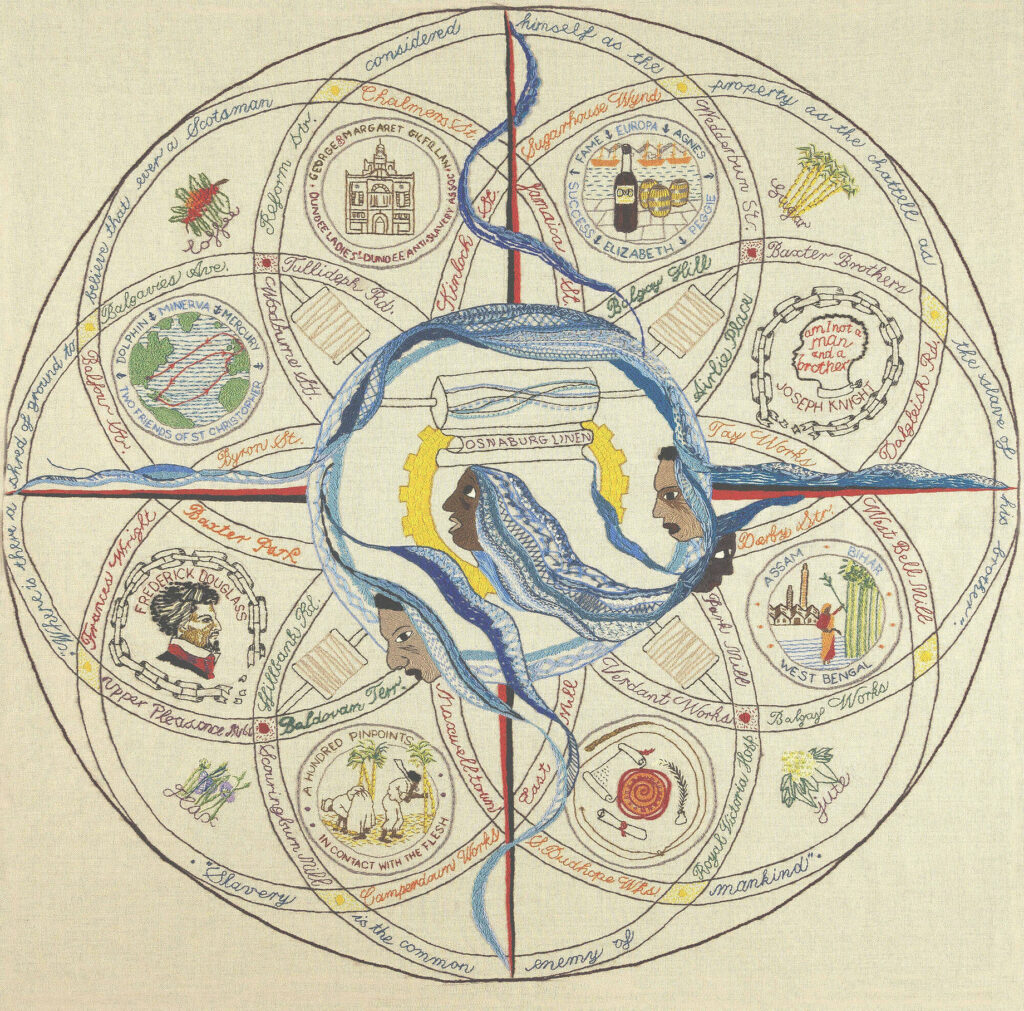

Osnaburg linen is the name of a rough, cheap linen cloth that was used for slave clothing. It was deliberately made as cheaply as possible, and was processed as little as possible, leaving bits of flax seed stuck in the cloth.

The flax seeds made the clothing rough and horrible to wear – like ‘a hundred pinpricks’. This image is from the Dundee Tapestry, currently on display at the V&A museum.

There is an Osnaburg street in Forfar. It was made in many places in Scotland before being exported to the colonies. Scotland used to have a thriving flax-growing and linen spinning industry. Of course, linen was worn by everybody, of every social class, but it would not have been like Osnaburg.

Herrings – salted herrings were exported from Scotland as food for slaves. Girls and women were employed all over Scotland in the herring industry. Mallaig was a major port for the export of herring.

Jobs – Scots were employed as soldiers, clerks, overseers and all kinds of jobs in the colonies.

Consumers – tea, sugar, tobacco and cotton were everyday essentials, which even the poorest person would have some access to. Therefore, as working class people are the majority in the population, the market for these goods was vast.

We’re going to learn more about the Age of Empire by looking at three major traded goods: sugar, tobacco and cotton. The story of these common items is full of human suffering.

Sugar

What does sugar look like today? If you were to buy some in a supermarker, what would it look like?

It comes in other forms too – syrup, cubes, powdery icing sugar.

It’s in loads of foods, such as ketchup, baked beans and breakfast cereals. Is it good for us? No!

What do you think they used it for in the 18th & 19th centuries? It was put into tea, coffee, baking, jam making – and rum. Sugar was sold as ‘sugar loaves’, solid domes of sugar.

In the 17th and 18th century sugar plantations in the West Indies supplied Britain with sugar. By 1750, there were 120 sugar refineries operating in Britain and prices were very high. Vast profits were made in the sugar trade, to the extent that sugar was called “white gold”.

The demand for sugar was huge. But the human cost of producing it was also huge. Life expectancy for a slave working in the plantations of the Caribbean islands was around three years. They died from overwork, tropical diseases and accidents – sugar processing was very dangerous.

In fact, it wasn’t even possible to make enough sugar to meet demand.

Many Scottish men and their families took jobs out in the Caribbean. It is said it was easier for an educated Scot to get a clerical job in the colonies, than in London where they were discriminated against. However, other Scots took jobs directly involved in cruel practices, such as ‘overseers’, forcing the enslaved people to work to exhaustion. Thus these Scots became part of the slave economy. These were not rich gentry, but ordinary people, hoping to make a bit of money and then come home. But tropical diseases were a constant danger, and around half of the Scots that went to work in the Caribbean colonies died there.

Tobacco

Tobacco was used by almost all men, from the poorest to the richest. It was smoked in pipes, chewed or taken as ‘snuff’ – yuck! You can see the fancy ‘snuff mulls’ upstairs in the museum. Poor men smoked simple clay pipes. In fact, broken clay pipes are the most common object handed into the museum!

When tobacco first started coming in from America in the early 1600’s, King James thought it was disgusting, and wrote ‘A Counterblaste to Tobacco’. He claimed it was a filthy, smelly habit and very bad for health. Was he right?

Here are some pictures of tobacco being grown in America, at Colonial Williamsburg where people have preserved the trades and crafts of the 18th century. It’s a living history museum, a bit like the Highland Folk Museum at Newtonmore.

Glasgow was the port which imported half of Europe’s tobacco trade at this time, an industry which depended upon slave labour to grow the tobacco in Britain’s colonies in the Americas. The ‘Tobacco Lords’ of Glasgow made huge sums of money, and many of the grand buildings in Glasgow were built by these wealthy merchants.

The tobacco industry supported a great number of jobs here in Scotland, such as pipe making and ‘tobacco spinning’ which was preparing the tobacco for smoking in pipes. Many men in Lochaber would have been involved in trading in tobacco, snuff and pipes.

Cotton

Cotton was grown by enslaved labour on plantations in the American South, and to some extent the Caribbean.

Until the 19th century, linen was the commonest fabric, worn by all social classes as both under and outerwear. Wool was also universally worn. Wealthy people could also afford to wear silk. Advancements in cotton processing such as the ‘spinning jenny’ together with increased availability, meant that cotton replaced linen as the most common fabric. As with sugar and tobacco, the demand was almost limitless. The cotton industry became enormous. After all, everyone has to wear something!

Everyone wore cotton; it was used for bed sheets, tablecloths, curtains and baby’s nappies. Even poor people had second-hand cotton clothing.

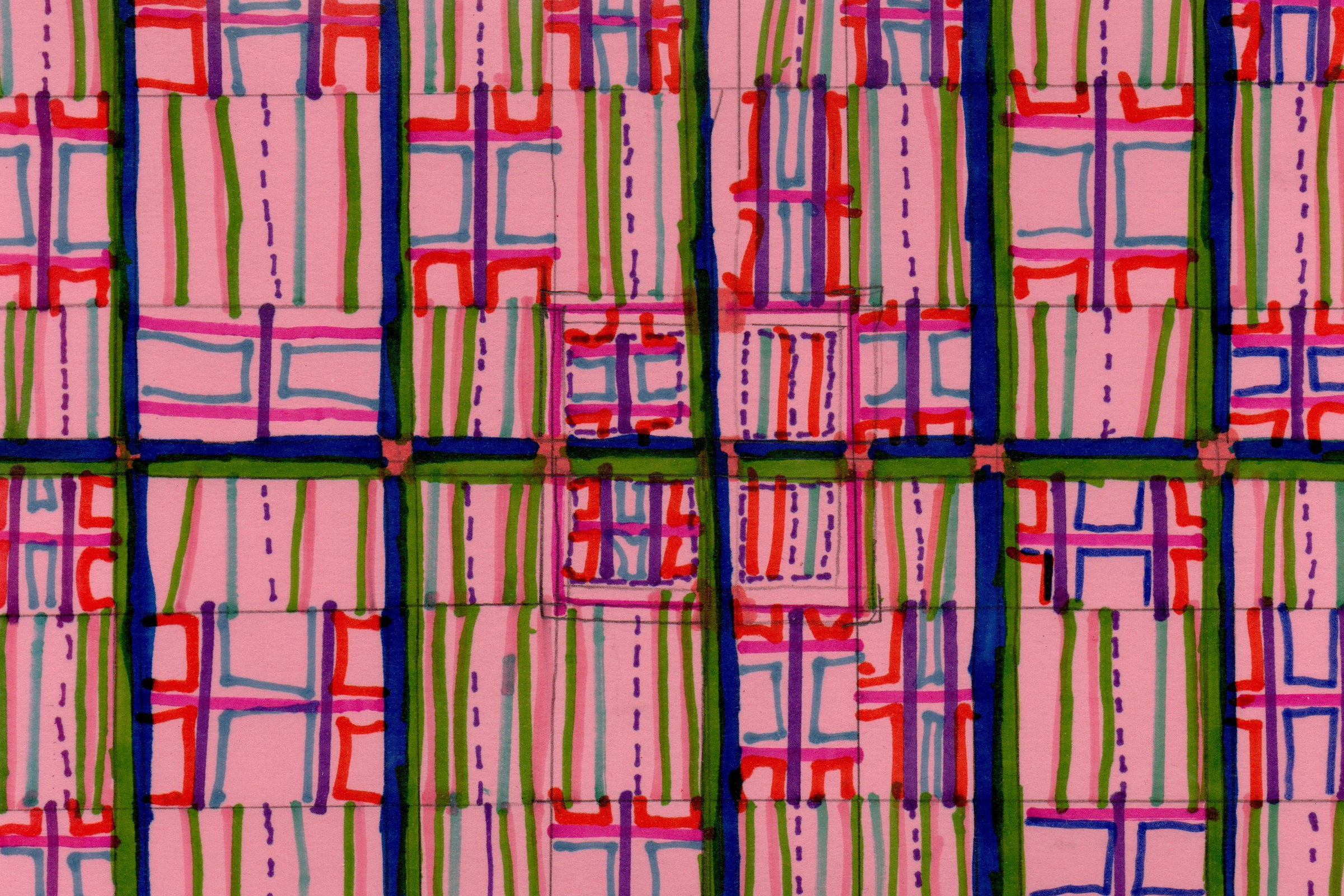

In the Caribbean, a new kind of cotton began to be worn by both enslaved and ‘free coloured’ women. Forbidden to wear hats, they used this beautiful ‘madras check’ cotton for head wraps. This fabric could not be more colonial. Originating in India, often with simple stripes, it was copied in the Caribbean, with its check designs inspired by Scottish tartan. It is now a powerful symbol of Caribbean culture, for example the traditional ‘douette’ dresses

Cotton was first imported into Britain from India, from the late 17th century onwards. The beautiful ‘painted chintz’ fabrics became a craze – everyone desperately wanted some of this lovely soft, colourful fabric for clothing and house furnishings. The British weavers got very angry as their cloth was less popular, and laws were even passed banned the import of Indian cotton. However, the British merchants continued to trade in Indian chintz, selling it to the American colonies, and, much worse, using it as a currency to buy slaves. One merchant said ‘Slaves, after all, could only be gotten by exchanging them for the cottons from India’.

These are the kind of ‘trade cloths’ which were so desirable with the African slave traders.

But!! The British were determined to make their own cotton so they could make lots of money from this desirable product. Cotton plantations sprang up in the American colonies, which used slaves to do all the hard work.

At the same time, in England and Scotland, machinery was invented to process cotton much faster than human hands. In a strange twist, it was now Britain exporting machine-made cotton to India!

Slavery was officially abolished throughout the British Empire in 1833. However, raw cotton grown by slaves in America was still bought by British merchants, making vast fortunes for those involved.

The West Highlands

How was the West Highlands involved in any of this?

Highlanders were both victims and perpetrators in this Age of Empire.

As you know, the Gaelic-speaking crofters were forced out of the glens, often overseas, against their will. Many ended up working in industries, for example in Glasgow, that were associated with colonial trade, though of course they had no choice.

Many Highland men joined the army just as a way of earning a living, and ended up fighting for the British Empire.

Wealthy landowners in the Highlands, however, were often guilty of profiting directly from slavery.

Many Highland estates were bought with money gained from plantations in the Caribbean.

This slave token was found at Garvamore.

For example, in the 1820’s, the brothers Angus and Evan Fraser from Fort William owned plantations called ‘Ridge’ and ‘Pleasing Hope’ in Demerara, and became wealthy merchants.

We can still see the effect of this today in the Highlands; there are many huge private estates, and the owners don’t even live there. There are important questions of land management and environmental concern on these estates.

The wealth and advancements in technology brought roads, bridges, canals and railway to the Highlands – but it was a devastating time for the Gaelic-speaking Highlanders.

This era ushered in the modern age – but at a great cost to so many human beings.

Want to learn more?

Scotland and Slavery: article in BHM24 Click here

Slavery and the Highlands: article by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh Click here

Entangled histories: the Highland Clearances and the transatlantic slave trade: article by Harvey Dimond published by Art UK Click here

See in the museum?

Slave token, made of metal, found on the British Aluminium estate outside Fort William. Not on display, but can be brought out for school workshops.

Sugar loaf cutters, used to pinch off a serving of sugar. On display in Room 7.

China plate, 18th century. Chinese export porcelain was often ‘armorial’; made for gentry families and bearing their crest. This plate belonged to Sir Archibald Campbell of Inverneil, who joined the East India Company in 1768 and became Chief Engineer in Bengal.

18th century bowl, made of coconut which would have been an exotic item, sourced through colonial trade. It is inlaid and mounted with silver. Engraved with ‘’O’Hara Kene to Dr Samuel Johnson with many thanks 1764’.

Interesting places to go

New Lanark Mill, a former 18th century cotton spinning mill village. This superbly preserved site has UNESCO World Heritage status. While not in Lochaber, many displaced West Highlanders sought work in textile mills in the central belt of Scotland, working with slave-grown cotton.

Glasgow City of Empire: permanent exhibition in the South Balcony of Kelvingrove Museum, Glasgow.

Activity suggestions

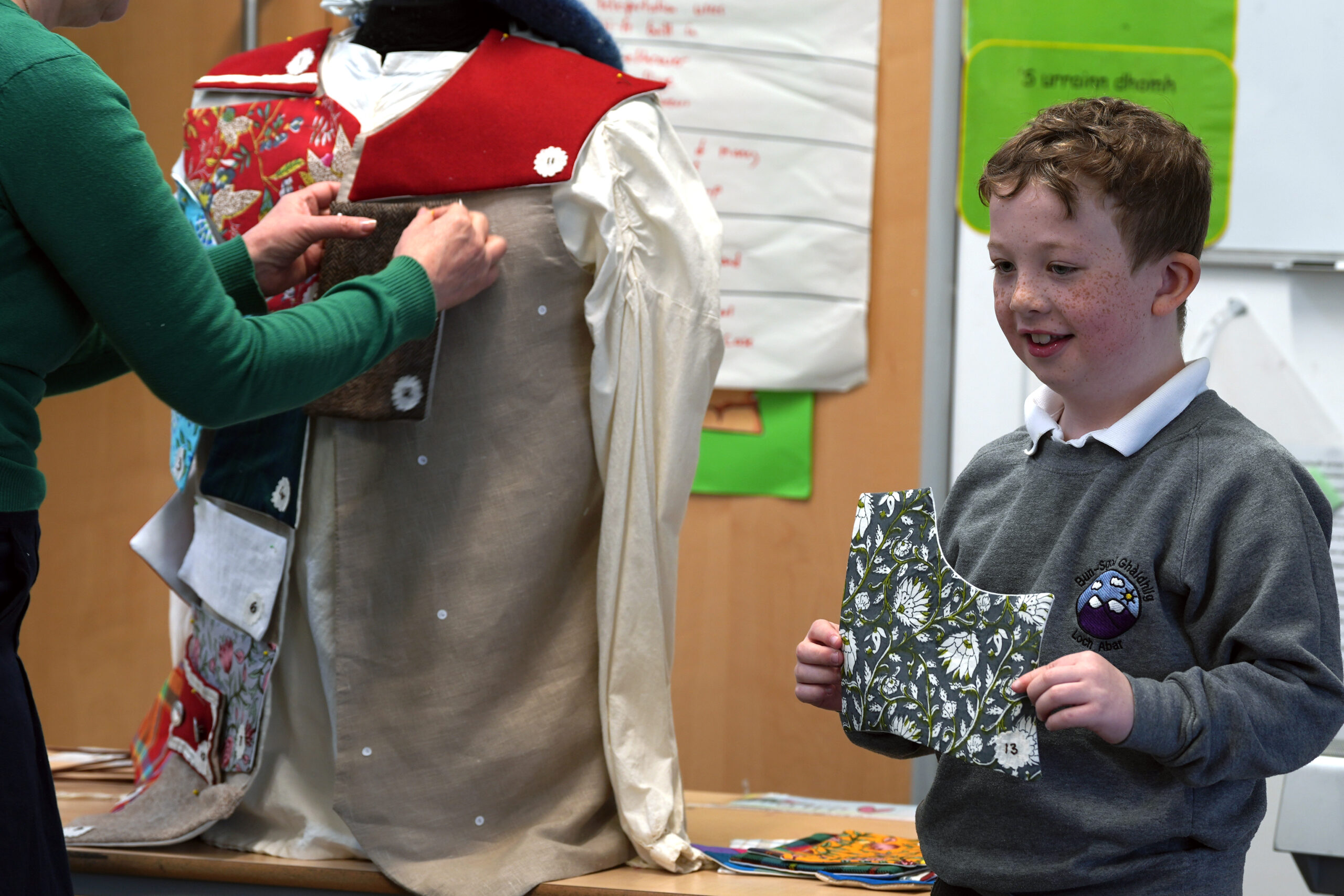

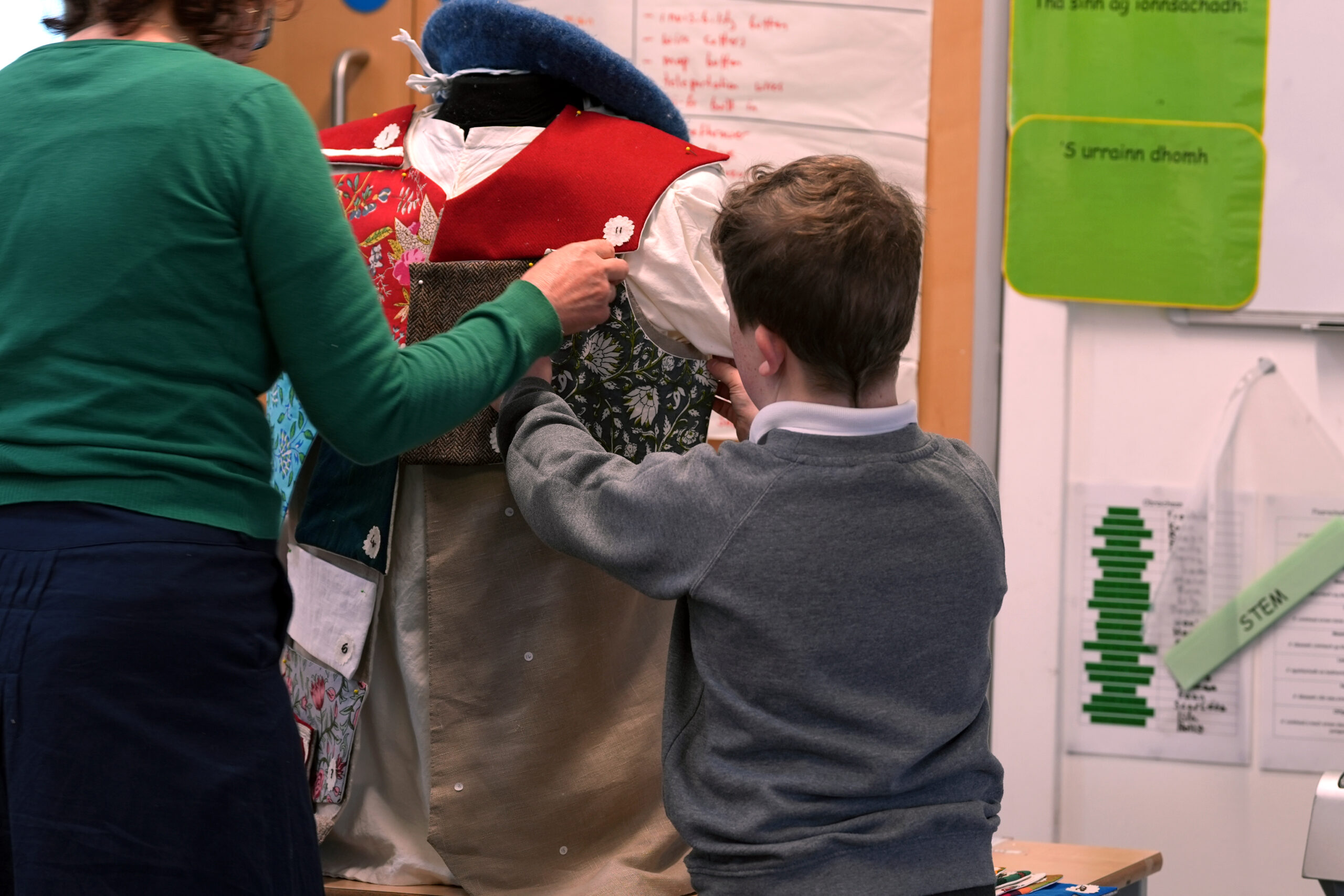

Design a patch which could be added to ‘Jamie’ (see below). Under your drawing, describe how the fabric you have drawn is part of the colonial story (for example, madras check or Indian block print cottons)

Put a big world map on a wall. On small pieces of paper, write short notes about what happened during the Age of Empire in different places, and pin them to the countries where these things happened. Alternatively, you could do the same but with QR codes leading to what you have written or recorded.

What did our partner schools do?

All the pupils took part in a workshop presented by the WHM learning team. This included object handling and discussions of the issues raised in this topic, which still affect people’s lives today.

We are very grateful to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation for the gift of tobacco leaves to the West Highland Museum. These leaves were grown and prepared using 18th century methods. A sheaf of 5 cured leaves is wrapped at the stem with a 6th leaf. In the 18th century, many sheafs like this would be crammed into huge hogshead barrels, then loaded on to ships bound for Glasgow. Tobacco use was universal among men in Lochaber at this time.

Pupils also all had a chance to add a piece to a special jigsaw puzzle..introducing Jamie!

This 18th century-style men’s waistcoat was designed with detachable, numbered patches. These colourful patches were made from fabrics which help to tell the story of the Age of Empire. The children had to find the correct place for the patch they were given, on the waistcoat. We decided to call the mannequin Jamie and gave him a blue bonnet!

Children in the museum learning about the tobacco leafs.

Tartan designs created my the pupils.

A virtual tour of the WHM 100 objects.

Children visiting the West Highland Museum learning about this time.