The Clearances

The emptying of the glens

‘The ancient proprietors of the soil shall give place to strange merchant proprietors, and the whole Highlands will become one huge deer forest; the whole country will be so utterly desolated and depopulated that the crow of a cock shall not be heard north of Druim-Uachdair; the people will emigrate to Islands now unknown, but which shall yet be discovered in the boundless oceans’

Prophecy by Coinneach Odhar (Dark Kenneth) known as the Brahan Seer, made in the early 17th century.

The Highland Clearances are one of the most significant events in Scotland’s history – and also one of the saddest.

The First Phase

People were forced out of the glens where they had lived for hundreds of years, and given small, useless bits of land by the sea. It was impossible to make a living by crofting on this marginal land; there was not enough grazing for sheep and cattle, and not much could be grown.

Here is a very special piece of art, made in embroidery by WHM Education Officer and textile artist Claire MacLeod. It shows the little strips of land on which the evicted crofters were expected to make a living

Traditional crofting practices such as ‘transhumance’ – moving the herds of animals to mountain pastures during the summer months – were now impossible. If you go for a walk anywhere in the hills of Scotland, you will come across the ruins of ‘sheilings’ – little stone houses where the crofters lived during the summer grazing.

The people toiled to make a living by kelp harvesting – collecting seaweed from out of the sea. Have you ever gone swimming off a beach here? The water’s freezing isn’t it!

It has been said that at the height of the clearances as many as 2,000 crofter cottages were burned each day, although exact figures are hard to come by. Cottages were burned to make them uninhabitable, to ensure the people never tried to return once the sheep had been moved in. Cottages were also ‘tumbled’ – destroyed.

They say the smoke on the Isle of Skye could be seen from 60 miles out to sea.

The Second Phase

Now people were forced to emigrate. They were given notice to assemble on a certain date at a pier, told they had to leave most of their possessions behind, and get on a ship bound for the other side of the world. In some cases, landlords agreed to forgive all debt if tenants emigrated.

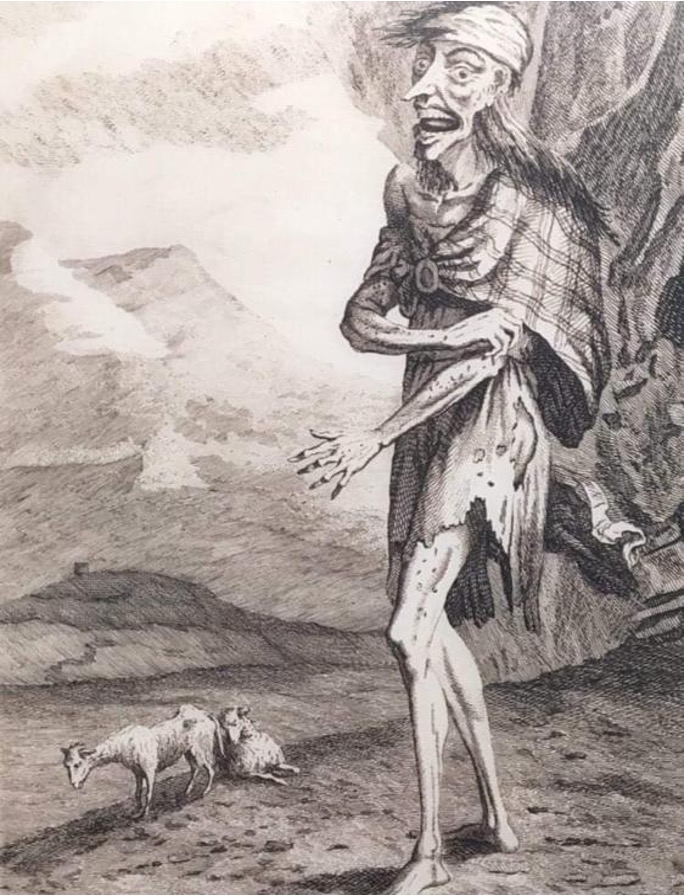

This famous painting is called The Last of the Clan. It shows the sorrow of the people being made to leave Scotland. They did not choose to leave.

Here is another called Lochaber No More, also very sad. Notice some of the objects are similar to ones we have in the museum.

It’s estimated that at least 200,000 Highlanders were forced off their land, with at least 70,000 of those forced to emigrate.

Where did they go? Many went to cities such as Glasgow, but also to Canada, United States, Australia, New Zealand.

Many Highlanders ended up in Nova Scotia – New Scotland. There are still Gaelic speakers there today.

Why those places? The answer is closely linked to the British Empire.

The countries that welcomed exiled Scots had established settler colonies in these places. It is sad that Highlanders ended up displacing indigenous people in places where they settled.

There is evidence of Highlanders learning indigenous languages, and marriages between them and indigenous people. The Gaelic term for an English person “Sassenach” closely relates to the Algonquian word for white man “Saganash” and may have been adapted from Gaelic, indicating friendship and communication, even with Scots who ended up in the army. But, generally, colonialism was a disaster for native populations, and they are still very marginalised today.

This beautiful beaded purse in our museum’s collections was made by Iroquois Indian women, and shows trade with Scots, which may have been sent or brought back as a gift.

Research shows that during the Clearances, at least half of the West Highlands and Islands, or almost 10% of the land of Scotland, was sold to people who became rich from slavery. These lands were purchased with wealth from the slave trade, including money paid out by the British state compensating slaveowners for their “loss of property” after the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.So tens of thousands of Highlanders were evicted from their homes by people who bought their land with money gained from slavery. We have a slave token here in the museum which was found on an estate.

The descendants of Scots around the world is called the ‘diaspora’. As the diaspora grew, Highland culture spread all over the world. There are clan societies and Highland Games wherever Highlanders settled.

Many of the American tourists who come here in the summer have Highland roots, and so visiting Scotland really means a lot to them. Let’s be nice to them!

But what was lost when so many people were evicted from the glens? Gaelic was intrinsic to the crofting way of life, and the Clearances had a severe impact on Gaelic language and culture. It has been declining since those times, and it is only in recent years that huge efforts have been made to support and save it.

Some of you are attending Gaelic school, and I hope you continue to use your language throughout your life. Maybe you will have a career with Gaelic!

The landscape of the West Highlands has also changed dramatically. Lochaber glens were full of deciduous trees, and the treeline was two thirds of the way up the mountains. Nowadays, glens are quite barren, especially where they are used for hunting estates, and unnatural plantations of ‘Christmas trees’ – conifers such as non-native Sitka Spruce.

So, the descendants of the Clearances may be doing well today, but we must never forget that this event changed the character and culture of the Scottish Highlands forever.

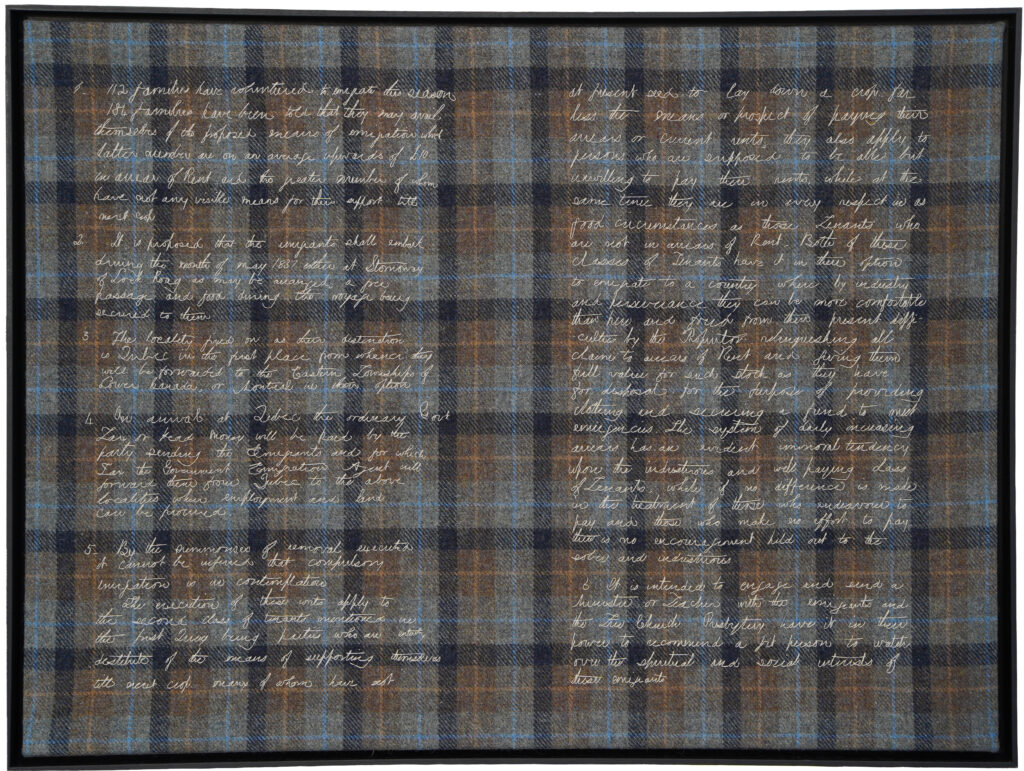

Here are images of another of Claire’s artworks, titled Notes on Emigration.

Highland Cow / Bò ghàidhealch.

Highland Cow / Bò ghàidhealch by Tamsin from Bun-Sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar.

A tour of a reconstruction of pre-clearances township.

Want to learn more?

Children of the Clearances, novel for children by David Ross

The Changing Highlands: Understanding People in the Past: The Changing Highlands: Clearances and Crofting, book by Iain Johnston

The Desperate Journey, novel for children which tells the story of the Clearances as they affect one small family.

See in the museum?

The Highland Life gallery, in Room 7 of the museum, is full of objects relating to the crofting way of life and Gaelic culture.

A ‘tairsgeir’ or peat cutter. This large wooden tool has a broad iron blade on the end. It is still used today in the Hebrides to cut peats. The peats would then placed in a heap behind a house, called a peat stack. Peat was burned for fuel, especially in the Hebrides where few trees grew.

A wooden ‘cheeser’ from Ardtornish estate. Cheese was made everywhere in the Highlands. Milk was left to sour for a day at room temperature and the curds naturally separated from the whey due to bacteria in the milk. The curd was wrapped in a cloth and put in the top of the cheeser. A weight was placed on top which strained the watery whey through the holes.

Beantag or winnowing fan, used to separate grain from chaff (outer casing of the grain), dirt, and dust. The beantag would be shaken so the unwanted material would blow away and the heavier grain would fall back down.

Knitting belt. This was used by crofter women who worked very hard, and knitted constantly. This leather shaped needle rest allowed a woman to knit even while walking, often with a heavy basket of peat across her shoulders.

Interesting places to go

The Highland Folk Museum at Newtonmore has a reconstructed Black House village. You can go into the houses and barns and experience being inside a real crofter’s house.

The Skye Museum of Island Life is set in thatched croft houses and a wealth of information on how crofters lived.

Arichonan Township: ruins of a cleared village, Argyll. Click here

Look out for ruined sheilings when you are out in the hills.

Activity suggestions

Draw, paint or collage 2 pictures, showing a glen before and after the Clearances.

In groups, say or write down three things which changed forever because of the Clearances.

Imagine yourself stepping off a sailing ship on to a strange land, perhaps Canada or New Zealand. Describe what you would see and how you would feel.

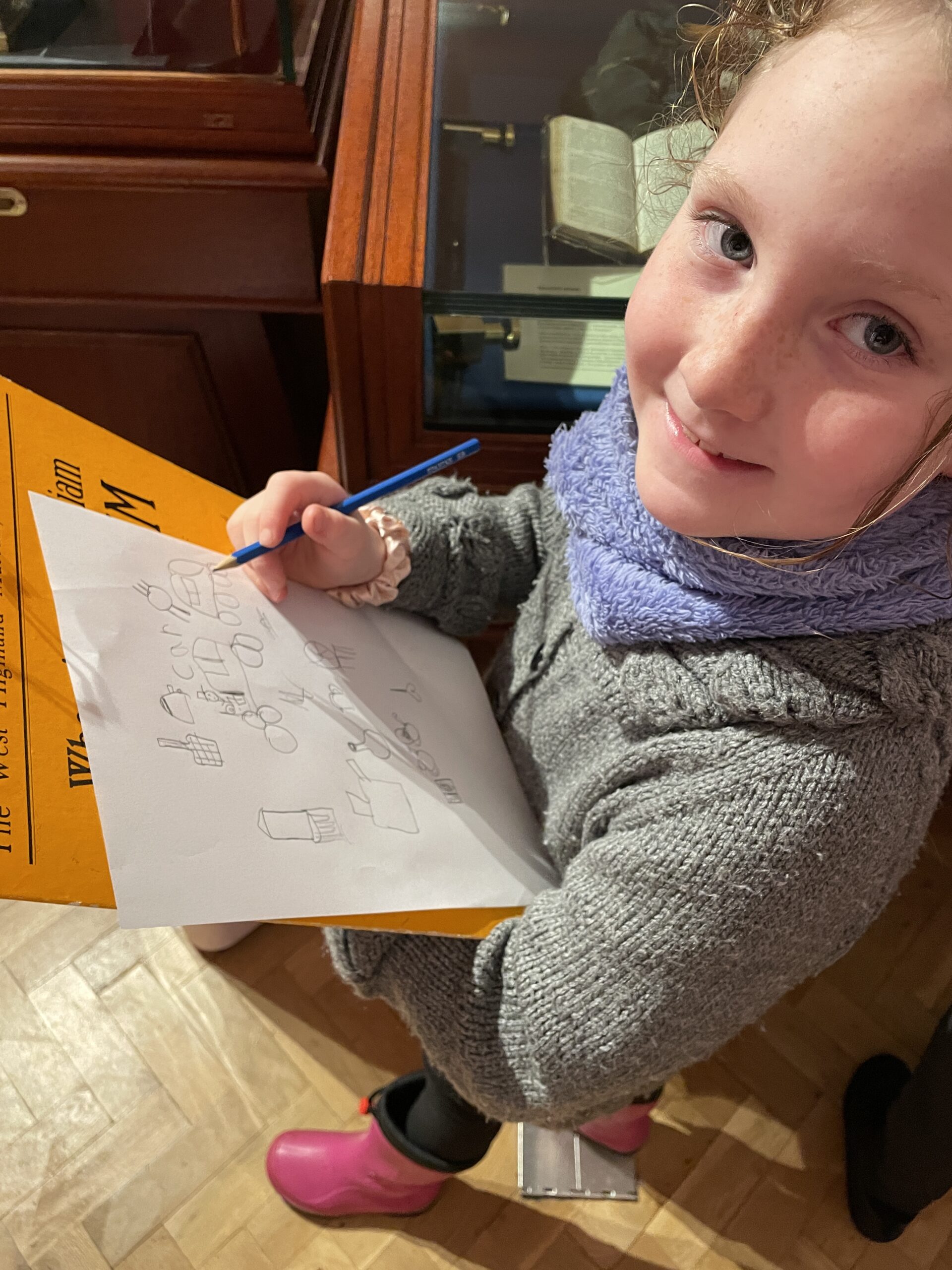

What did our partner schools do?

All pupils were taken on a field trip to the West Highland Folk Museum, Newtonmore, to visit the blackhouse village.

Pupils in p.6 at Lundavra school made papier maché models of burning croft houses, together with poignant stories written from the point of view of those who suffered brutal eviction.

Our young learners visiting The Highland Folk Museum and West Highland Museum.

A gallery of models made by pupils from Bun-Sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar.